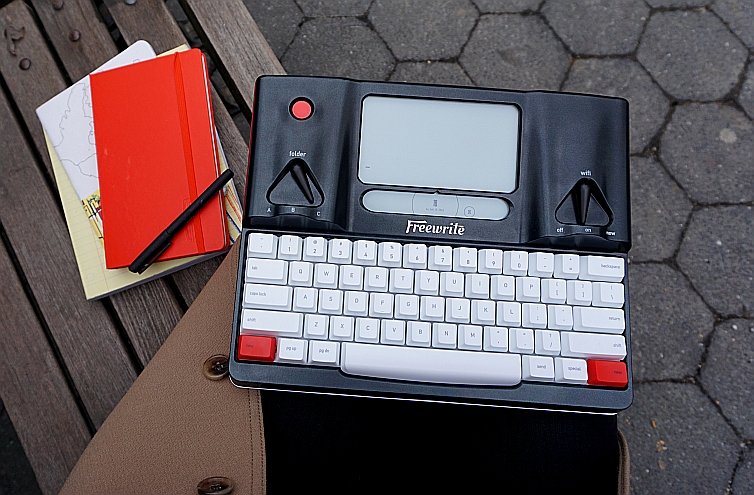

There’s a new piece of kit in the Performance Communications office: a Freewrite smart typewriter.

It’s a pretty simple piece of technology: a chunky keyboard bundled with an LCD screen and storage. It doesn’t have a spellchecker, a web browser, or a scrollbar. If you’re old enough to remember, it’s reminiscent of early pre-PC word processors. When you boot it up, you’re greeted with a blank screen – as you type, you’ll only be able to see the last three lines you’ve written

So, it just seems like an objectively worse version of a laptop running Word, right? So, why bother?

That depends on what you think a smart typewriter is for. It’s not designed for producing copy ready to send to the boss, client, or editor. Instead, it’s designed exclusively for one thing and one thing only: drafting.

Today, the biggest difficulty for most writers is getting started and getting something down on the page. And while it’s not a new problem, this blank page syndrome is especially acute as a result of how we approach writing today.

Historically, writers treated drafting and editing as distinct activities. The purpose of a draft was never to produce publishable copy. It was supposed to be dirty, full of typos, and areas for improvement.

Or, in the immortal words of Hemmingway: “The first draft of anything is shit.”

There was a point to this. Firstly, it encouraged you to get some copy on the page to play with. But, even more importantly, dedicated drafting forces you to commit to your train of thought.

Writing is thinking. The act of writing is not just an exercise in expressing ourselves – it’s a way to turn our fuzzy intuitions, opinions, and arguments into linear, sequential claims that can be communicated through the written word.

To engage in this long-form thinking, however, we need to usually stick to it – across sentences, paragraphs, and sections. For the reader, we need to make sure every word, sentence, and paragraph follows from what has come before. All our claims or conclusions need to be connected to what’s been said already.

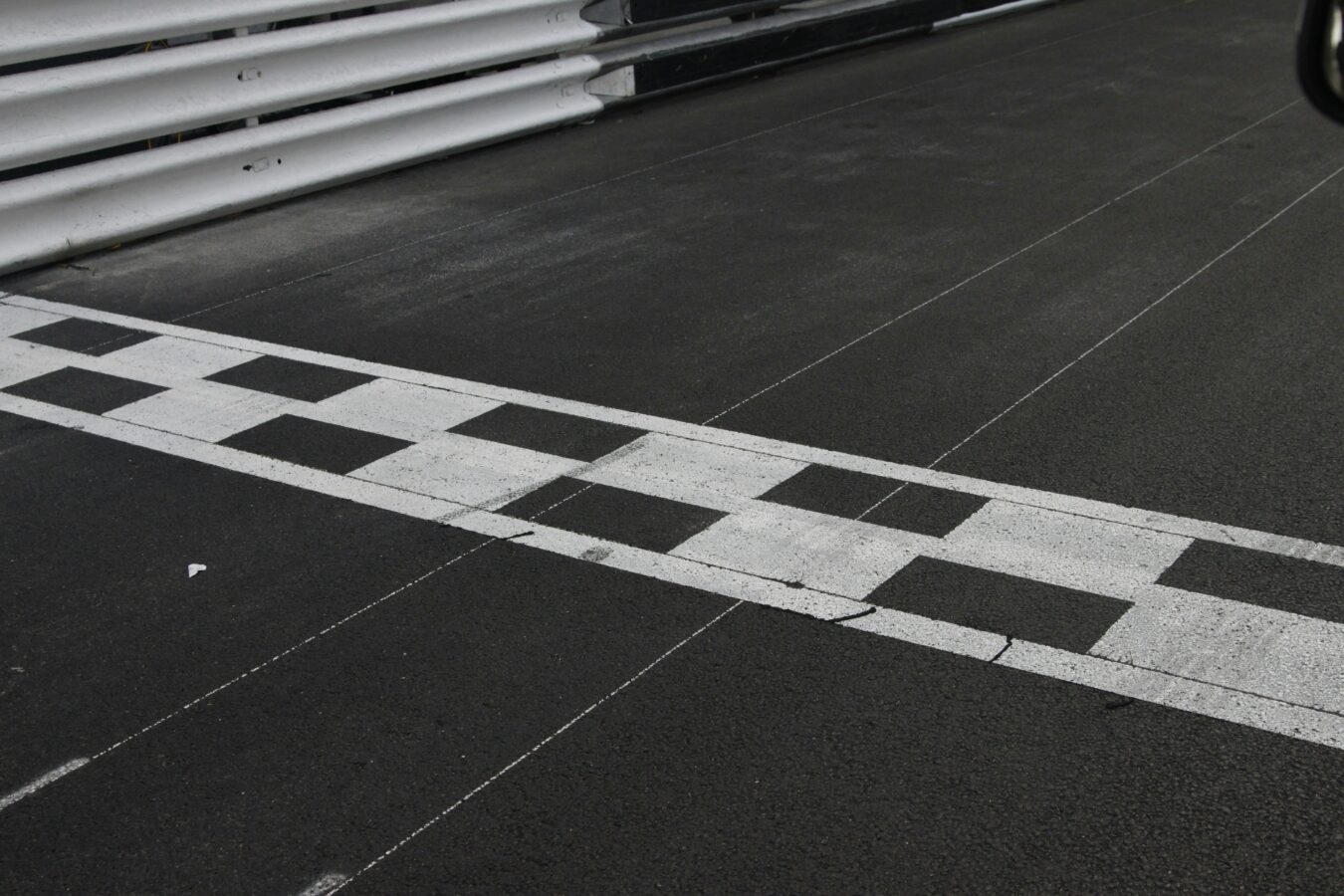

This is what we often call flow. And good flow is at odds with the stop-go drafting and editing that we often do on our computers. By being continually pulled out of the holistic train of thought for the full piece, a Word document encourages you to step back – to continually tweak and optimise individual chunks.

Computer-based drafting encourages us to agonise over individual sentences or paragraphs before pressing on. Even if you were to turn off your WiFi and your spellchecker, the fact that your peripheral vision is filled with copy means you’re prone to distraction. We can be paralysed if confronted with too many decisions, so is it any surprise that a screen full of text causes us to stall?

Instead of seeing a written piece as a cohesive whole that looks to justify a claim or conclusion, stop-go editing and drafting makes us look at it as a series of paragraphs and sentences in isolation. The result? The overall article stumbles, filled with non sequiturs and abrupt pivots in direction. Rather than taking a reader on a journey, it becomes a showcase of awkwardly connected Lego bricks.

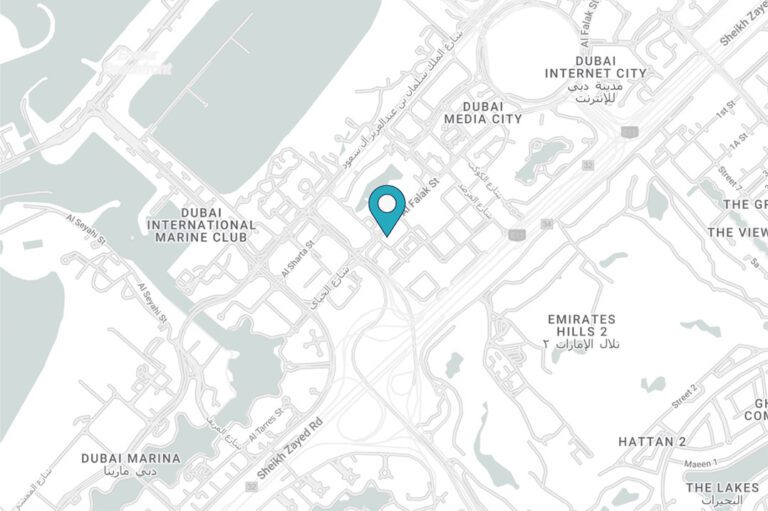

The marketing material for Performance’s new smart typewriter talks a lot about how it enables distraction-free writing. A lot of us only think about this in the context of getting content out the door, fast. But there’s far more to it than that.

We are a communications agency. Our central skill – the thing that adds value to our clients – is our ability to communicate. Tools like a smart typewriter are valuable because they offer the chance to make us more productive. But their most important contribution is to force us to be better communicators in the first place – and in a world swimming in bland AI-generated copy, that can only be a good thing.

Matthew Kirtley

(Drafted on the new Performance Smart Typewriter)